February 11, 2011

Op-Ed on Prisons in Panama: Tragedy at Tocumen, A Call for Real Reform

The following Op-Ed appeared today in La Prensa, Panama’s main newspaper. It was written by Jim Cavallaro, Executive Director of the Human Rights Program, and María Luisa Romero, JD ’08, who has been working with the International Human Rights Clinic on prison conditions in Panama since her 2L year.

A fire in the Juvenile Detention Center in Tocumen, Panama, last month claimed the lives of five teenagers. The fire was apparently caused by tear gas bombs. Reports indicate that the police laughed at the teenagers as they burned. The Panamanian government has responded with promises to improve prison conditions, including plans to increase capacity through the construction of new centers.

For those unfamiliar with prison dynamics, the promise of more and better infrastructure may seem like an appropriate response to the problems of the Panamanian prison system. Although improvements in infrastructure would improve the situation to some extent, the construction of new prisons is an inadequate response, and one that appears to repeat unfortunate pattern in Panama.

For the past five years, the International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School has been studying and documenting conditions in the adult prison system in Panama. In 2008, the Clinic published an exhaustive report in which we documented not only overcrowding and unhygienic conditions, but also profound institutional failures. Rather than professional guards, internal prison security is often left to police officers, who are not trained for this work.

We documented reports by prisoners that police threw tear gas bombs into the prisoners’ cells, and we also observed evidence of this inhumane practice ourselves. We called attention to marked inequalities in the treatment of prisoners, inequalities fostered by prison administrators and others in charge of guarding detainees.

We offered a broad range of measures necessary to bring Panama closer to compliance with its own law and international standards on detention conditions. These recommendations were the product of two years of research throughout the country, including interviews with hundreds of detainees, prison and judicial authorities, members of civil society and experts on prison management. Infrastructure development was, indeed, one recommendation we made. But it was only one of more than forty suggestions. The fundamental problems in prison administration in Panama, we concluded then, could not be resolved by building more prisons alone. We presented this argument to Minister Méndez and her team during a meeting this past December.

Successful prison reform requires difficult measures. These measures include the dismissal of corrupt officials, as well as guards and police who use excessive force against those whom they are supposed to protect; the establishment of standards for transparency in prison administration; the establishment of guidelines for prisoner rehabilitation that include the right of prisoners to an education and that ensure that those incarcerated leave prison with concrete opportunities to find decent jobs that will provide them dignified lives; and the investment of time and human resources to ensure that administrators, social workers and guards are well trained. Building detention centers is often much easier and much less controversial.

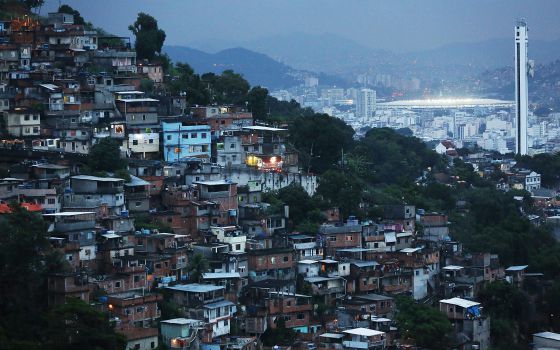

We do not doubt the commitment to prison reform and the good will demonstrated by Minister Méndez and her team. A prison training academy and improved rehabilitation programs are steps in the right direction. But we are concerned about the emphasis the government is placing on the issue of prison infrastructure. The emphasis has failed elsewhere in Latin America—most notably, perhaps, in Brazil, where the state of São Paulo initiated a massive prison construction project in the 1990s only to see prison overcrowding and violence reach record levels a decade later. That violence culminated in the May 2006 uprising that paralyzed South America’s most important city.

Everything indicates that different, or even better, infrastructure would not have prevented the tragedy in Tocumen. Better training and better systems for prosecuting and controlling abuses, along with a deeper and more serious commitment on the part of those who guarded these young detainees would have gone much further. We urge the government to learn the right lessons from this experience. The incident at the Tocumen Center was a tragedy that many foresaw and that cannot be allowed to happen again.